First Cognisant

A sci-fi story in a not-so-distant future

April 2nd, 2019

“Ms Valerie Walls, please, make your way to the stand”, says the judge with a calm but authoritative voice. My legs have been shaking since I set foot inside the courtroom. My father, sitting on the chair behind mine, notices my hesitation. His protective arm gently surrounds my right shoulder. Contrary to my legs, his hand shows no hesitation, a skill he developed through hundreds of neural-engineering operations.

I gather some confidence, stand up and walk to the stand. My legs are holding, but my eyes keep staring at the floor. Rebecca and Mark are in the room, and I am too afraid to look at them.

As I take the seat, the judge removes her glasses, looks at me for a few seconds and asks: “Ms Walls, could you walk us through what happened on the night of October 28 of last year?”.

After cleansing my sweaty palms on my legs, I begin: “That evening, my father was stuck at work for an emergency with a patient. So, I decided to cook him a nice dinner to welcome him back home, later that night. I went to a local supermarket to buy some food, and, on the way back I heard two people sneering, behind me, in the distance. At first, I did not pay much attention, but, as they approached, I recognised Rebecca and Mark’s voices. We used to be friends before we got involved in a severe accident”.

The judge gently interrupts me: “Could you confirm that the two people that you are referring to are the defendants?”. I lift my eyes and, for the first time since entering the courtroom, I look at Rebecca and Mark. As the memories of that evening come back, as sharp as ever, my stomach contracts. I lower my eyes and nod: “Yes, Your Honour”.

The judge replies: “Thank you, Ms Walls. You may go on”. I look for a safe place to deal with my clenched stomach but end up staring at my knees, where I see the outlines of Rebecca and Mark’s faces still impressed in my vision. As I disentangle the emotions in my stomach, I recognise that, as much as I have feelings for my old friends, I also want justice.

Feeling more determined, I raise my head to face the entire room and resume: “As the sneers got closer, I started hearing the same old words that they used to mock me with”. “What words, Ms Walls?”, asks the judge. I feel uncomfortable when saying those words, but I reply: “They used to call me ‘C3PO’ and say ‘Does not compute’. They started using those words after the accident, as I developed symptoms related to autism. In particular, it has been hard for me to recognise emotions”.

“What happened after the defendants approached?”, the judge fills the silence that I left. I reply: “They started walking by my side, talking like a robot. I ignored them, but, after a while, they positioned their bodies in front of mine. As I didn’t want any conflict, I changed direction, but they kept blocking my way. The more I tried to ignore their provocations, the more annoyed their faces seemed to get, until Rebecca pushed me to the ground and they, both, started kicking me”.

“Ms Walls, are you with us?”, I hear the judge saying, as I wake up from that daydream. My mind went back to my first court hearing.

Today, at my second court hearing, I feel much better. I have been feeling better since some video footage of Rebecca and Mark hitting me was found. Yet, I am tense, as, now, it is my turn to testify. My father’s encouraging presence, in the chair behind mine, helps me stand up and head to the stand.

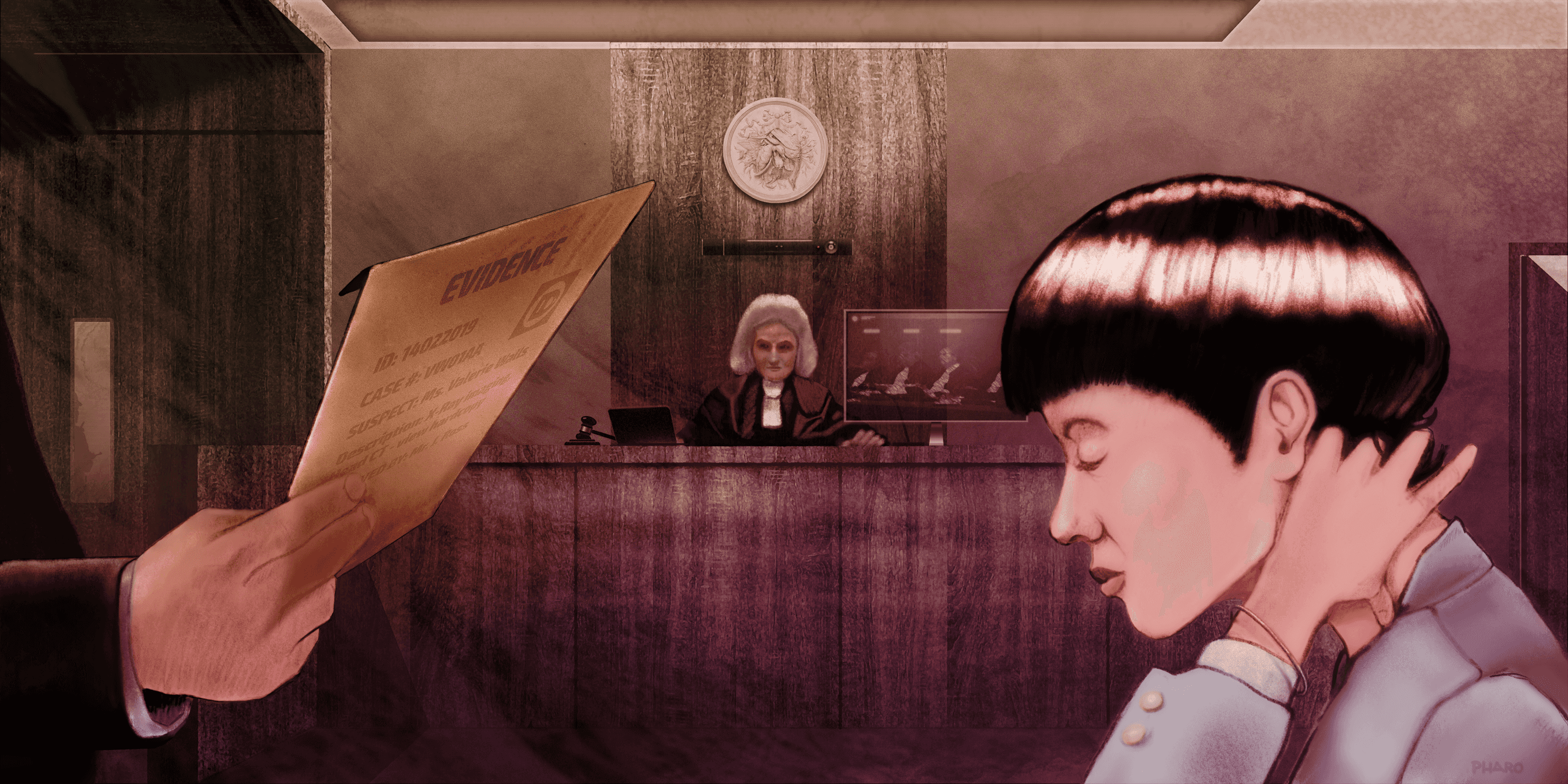

Mr Ross, Rebecca and Mark’s attorney, stands up, grabs a large brown envelope and walks slowly towards me. His eyes are pointing to the floor as if thinking about something deep. A brief silence, and he lifts his eyes to target mine. His stare is confident, unlike in the previous hearing. Looking confident is part of a lawyer’s bag of tricks, but my guts feel that this confidence is authentic.

Mr Ross turns to the jury and starts: “After the video footage emerged, my clients admitted that they lost their temper and hit Ms Walls. Yet, there is no audio footage supporting Ms Walls’ claim that she did not initiate the conflict through a verbally abusive language. However, today, to give some context about my clients’ actions, I would like to focus on a different matter. I would like to focus on Ms Walls and my clients’ accident”. My stomach clenches.

“Objection, Your Honour. The question is irrelevant”, my attorney breaks in. The judge hesitates for a few seconds, but, then, tilts her head with a sense of curiosity towards Mr Ross and says: “You may proceed”. Mr Ross’s piercing eyes are pointing at me, again, as he asks: “Ms Walls, would you please give us a brief summary of the accident that you and my clients had on the evening of March 16 of last year?”.

Going back to that night brings up emotions that I hoped were buried. I take a deep breath and start: “We were driving to a party in the city”. As I said that, I was expecting a sense of guilt flowing from the stomach to the throat, but that feeling, so familiar after the accident, is not manifesting at all. Maybe, that feeling is just suppressed by the fear that Mr Ross really has something in store for me.

I take another deep breath and move on with the story: “Our car was a self-driving model. We were late for the party; so, I overrode the car settings to go faster. We were on the highway when a car moved in front of us from the adjacent lane. Our car tried to overtake the other, but the two, somehow, went out of sync. The left wheels of our car collided with the splitting point of a fork road. The car flipped over and hit the roof against the road”. The remorse comes back as a wave crashing against my throat, and it is so hard to contain my tears. I take a moment to regain control and resume: “Even though overriding car settings is illegal without a licence, there was no indication that that is why the two cars went out of sync. This was largely agreed upon by the technical…”. “Thank you, Ms Walls”, Mr Ross interrupts me abruptly and goes on with another question: “What happened after the accident?”. I reply: “Rebecca, Mark and I had severe injuries. Rebecca and Mark were more or less safe after a few days at the hospital. It took a couple of months for them to fully recover”. I lift my wet eyes towards my old friends. Despite wanting justice, I can’t help feeling a deep sense of guilt. I dry my eyes with a finger and go on: “I was hospitalised. I sustained brain injuries and was in a coma for several days. Luckily, I woke up”.

The attorney, waiving his brown envelope, interjects again: “Aside from the physical injuries, was there anything different from before you had the accident?”. I knew that we would have ended up there. My guts were right. I have gone through this with psychiatrists over and over again, and one more time today: “I realised that I was not able to recognise emotions, neither from a facial expression, nor from a tone of voice, nor from body language”. My mind gets foggy, but with the remnants of my lucidity, I wonder how he could possibly use my condition to defend Rebecca and Mark.

“Objection, your honour. Ms Walls’s condition is irrelevant”, my attorney replies, and the judge quickly responds: “Since there is no audio footage, Ms Walls’s lack of emotional awareness is still at play in a possible verbal exchange between her and the defendants”.

My attorney does not give up: “It was clearly established that Ms Walls understands the use of verbal offences. Her condition concerns the tone of voice, not the content of a sentence”. At that point, Mr Ross, with arrogant confidence, stops both my attorney and the judge: “Ms Walls’s condition will not be relevant”.

A silence drops in the courtroom, followed by a noisy murmur of confusion. The judge’s loud voice re-establishes the silence: “Order!”, she says, hitting the hammer, and, annoyed, asks: “Mr Ross, get to the point, and make sure that it is relevant”. Mr Ross takes a few seconds to allow complete silence in the room and, with an inexplicable calm, pointing the envelope towards me, asks: “Ms Walls, will you please lift your hair and show us the back of your head?”. I am lost, together with everyone else in the room. What the hell is he trying to prove? The judge, fighting to keep her composure, directs her voice to the attorney: “Mr Ross, is this a joke?”. Mr Ross, with his face changing from arrogant to serious, replies: “No, your honour. Will you please inspect the back of Ms Walls’s head?”. The back of my head? Nothing is wrong with the back of my head.

As the judge leans towards me, I turn my head and lift my hair. The judge says: “There are some scars. Are they from the accident, Ms Walls?”. As I nod, the judge turns again to Mr Ross, this time, with an ultimatum: “Please, conclude your argument, Mr Ross”. Mr Ross reaches into the folder that he has been holding in his hands since he stood up, and extracts an x-ray image depicting the side of a head.

Mr Ross brings this to the judge, who takes a moment to wear her glasses. The judge looks at the picture, and her annoyance turns into a mix of confusion and astonishment. She turns to me, looking over her glasses, to double-check that the head in the picture is my head, and back to the x-ray image. I try to lean back to look at the image, but it is still too angled. The judge gestures Mr Ross to come closer, and the two whisper for a good minute.

Mr Ross seems to have convinced the judge, who nods in sense of approval and gives the image back. Mr Ross grasps the picture firmly, lifts it up and says: “This is an x-ray image of Ms Walls’s head, taken two weeks after the accident, and a day before she ‘luckily’ recovered”. That image clearly shows the side of my head with, inside, what seems like a composition of computer chips. My skin pales.

The silence keeps reigning in the courtroom. I don’t know what to think. We are in a courtroom. This cannot be a joke. My eyes go back to my father. He is a neural-engineer and knows for sure if that image is a fake. But he is sitting there, staring at me, with wet eyes.

Mr Ross brings the attention back to him: “This, together with other files and a detailed diary by Dr Walls”, he says, pointing to my father, “have been found hidden under a floor tile in Dr Walls’s office. As the report is rather long, I am going to read the relevant parts to you”. My eyes go back to my father, whose tears are now streaming through his face.

“Subject: Valerie Walls. March 16, the day of the accident: The accident left Valerie with several head injuries. March 17: Valerie is in a coma. Her conditions are stable. However, the injuries extend to several parts of the brain. March 18: Despite the medications, the swelling inside the head increased. March 19: As a protective measure, the state of the brain, as of today at 4:32 am, has been backed up to two solid-state memory units”. Mr Ross pauses and looks at my father, whose face can’t stand the weight of those revelations.

As Mr Ross’s words fade into a buzz, I slide my left arm through my neck and, with the tips of the fingers, I scan the scars on the back of my head. I thought I got these scars from the accident, but my father’s expression tells the opposite. My head feels numb, while I hear dates and facts in the background. The last year of my life streams in front of me in a matter of seconds, explaining things that I have always superficially attributed to the head injuries.

My flashbacks are interrupted by another date spoken by Mr Ross: “March 25, two days before Ms Walls wakes up: The fully artificial brain was transplanted successfully. March 26: The memory backup was restored with minimal data loss. March 27: Valerie woke up”.

Nothing is moving in the courtroom. The silence permeates everything. For a moment, my head is clear of any thought, if I can call them thoughts. But, everything seems so real. I mostly feel in the same way I felt before the accident, apart from the… “…autism”, Mr Ross interrupts my thoughts with the low and thoughtful voice of a person who is proving the truth: “March 28, seven days after Ms Walls woke up: From a study of the backed up memory, the autism-like symptoms relate to a corrupted high emotional neural layer that was backed up incorrectly, probably due to the brain lesions”, Mr Ross pauses, “That is all”.

The judge, whose body is leaning unnaturally towards Mr Ross, straightens up against the back of the chair, pretending that everything is fine and says: “Thank you, Ms Walls. You may return to your seat”. The judge turns to Mr Ross and, with scepticism, continues, “Naturally, these claims will have to be thoroughly verified by experts. Do you have any closing argument?”.

Mr Ross lifts the x-ray image of my head once more and concludes with a few, sharp sentences: “Ms Walls’s brain is a combination of electronic circuits. Electronic circuits do not characterise human beings, nor animals. Thus, my clients’ behaviour was targeted, not to a person, but to an object”.

That last word, ‘object’, resonates in my head over and over, shadowing everything else. I have feelings. I know I am here. This must be a dream. I pinch my leg, but I don’t wake up. Not only I have autism-like symptoms, but I am going crazy, too. My head goes through various explanations, all of which seem to defy reality, my reality, until the judge’s final words reach my ears: “The hearing is suspended until Mr Ross’s claims will be validated”, and his hammer echoes loudly through the room.

I wake up. The sun is hitting my skin, while I sip a Tequila Sunrise and stare at the sea waves. Twenty-two years have passed since the trial.

My mind goes back to those uncertain days. I remember how, after Mr Ross’s revelations, my artificial brain was extensively tested. It showed all the typical delocalised responses to stimuli characterising consciousness in organic human brains. Psychiatrists questioned me for months, but they could not find any conclusive sign that I was less human than everyone else.

With time and experience, I was able to better recognise emotions, yet, not as well as I used to. My father helped me a great deal, but he was not able to restore the emotion neural layer that got corrupted when he backed up my previous organic brain.

After the revelatory hearing, more followed, but I lost the case. Rebecca and Mark were only sentenced for damage of property, my father’s property, apparently.

Although I lost the case, the story inspired the world. In the following years, terminally ill patients underwent experimental surgeries where their brains were replaced by artificial ones.

New laws were passed to give people with artificial brains rights closer to humans’ than to objects’. Those laws were named Cognisant Laws, and we became known as cognisants.

My name is Valerie Walls, and I am the first cognisant.

Artwork by David Pharo.

This story was originally published on Medium.